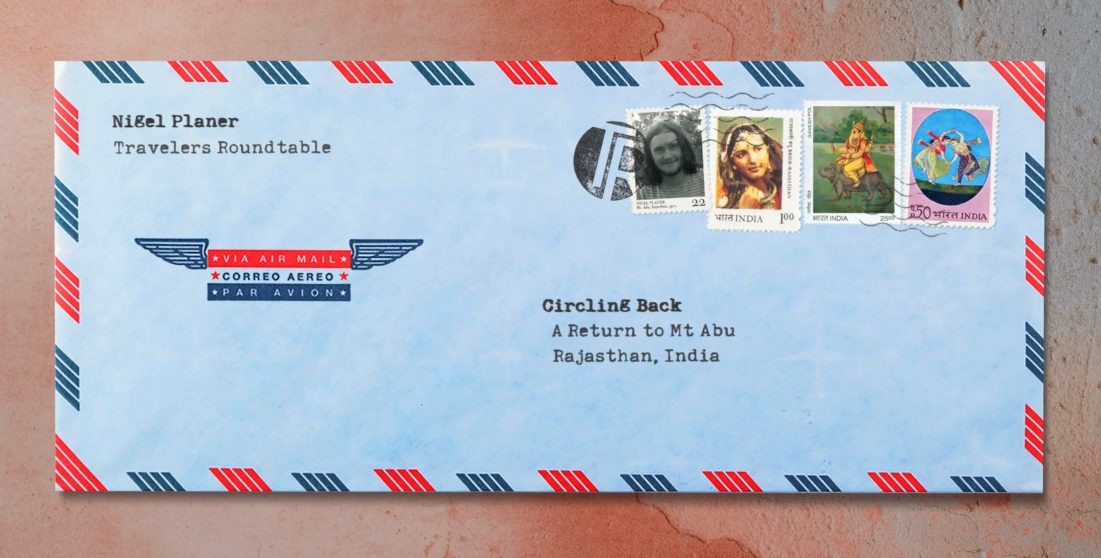

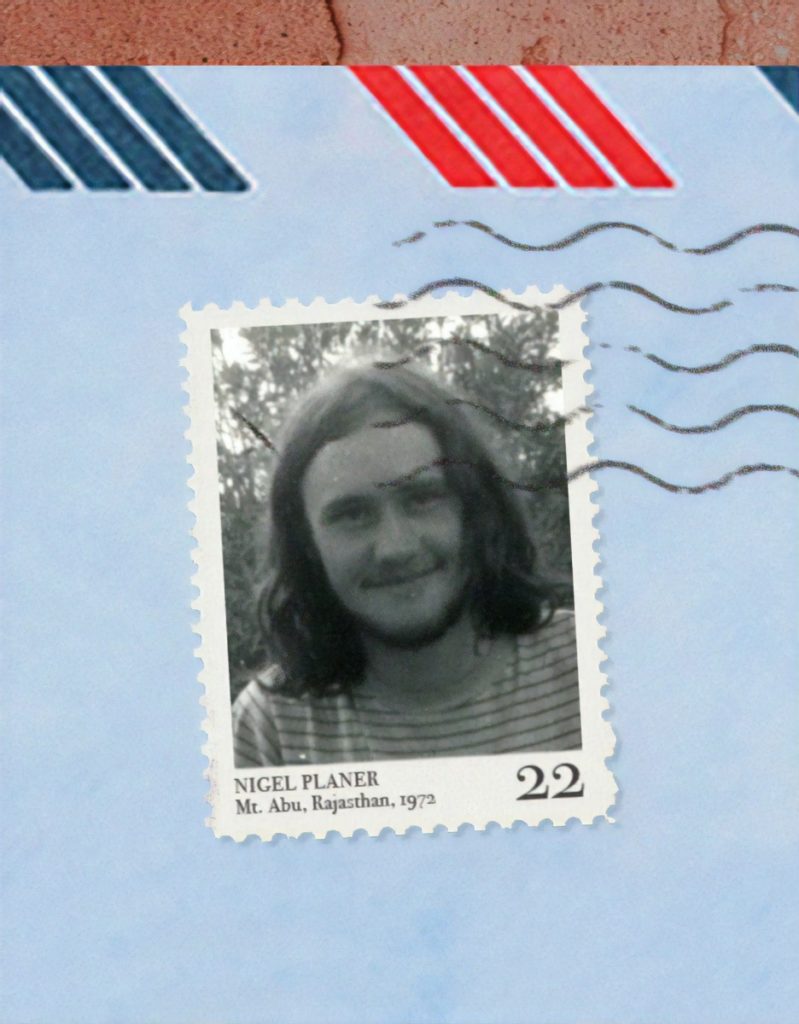

“When I was twenty, I dropped out of college and travelled alone, overland to India. I didn’t tell my parents where I was until, some months after my disappearance, I sent them – from Mount Abu – one of those thin, blue airmail paper letters.” Art direction and imagery by Kevin Grady.

It is Valentine’s day, and for the first time ever, an enormous multi-faith, multiple wedding has been arranged in Mount Abu, Rajasthan, and the whole town has come out to celebrate. It takes place in a big bowl of dust called The Polo Ground, so named in the days of the Raj when this pretty hill retreat was the holiday resort and sanatorium for British civil service officers and their families.

There is a festival atmosphere; the sun is shining in a pellucid sky, and the scene is abundantly colourful. The Polo Ground is surrounded by a row of numbered marquees in yellows, pinks and oranges, where one hundred and ten couples—from all castes and all religions—are due to be wed today. Excitement is tangible.

The man who organized it all—Dr. Gyan Prakash—assures us that all religions are represented there, although we do not see any of the surprisingly numerous Christian or Jewish Indians present. It is just a Hindu and Moslem affair, a noble thing in itself. And when he says “all castes”, I suspect he means there were marriages from all castes planned, not that there were going to be marriages between castes. The differences in the wealth of the families is quite apparent – some of the tent booths are much more lavishly decorated than others, with glittering silver ribbons and flags.

Nevertheless, there is an overwhelming feeling of universality and companionship. All the tents are shining and billowing in the breeze and the pale, translucent dust kicked up by the crowd catches the sunbeams.

An Auspicious Day

Dr. Prakash is a charming, twinkly man dressed in an immaculate white suit and tie. A retired Government Health administrator and ex-director of the Mount Abu Hospital, he is brimming with joy and pride at the achievement of this special day. “The astrology is auspicious for today” he beams.

Astrology is very important in matrimonial matters in India; the ads in the matrimonial pages of the Times of India, for instance, are always keen to stress the astrological positions of the potential bride or groom. Until recently, in hotel lobbies in Delhi and Mumbai, alongside the signs for “concierge”, “spa” and “reception” it was not uncommon to see a sign for “astrologer”. It may seem strange to westerners for a society to put so much store by something as unscientific as astrology, but then again, the world’s economists have not had a much better success rate at predicting the future, have they?

Wandering the Cheesecloth Road

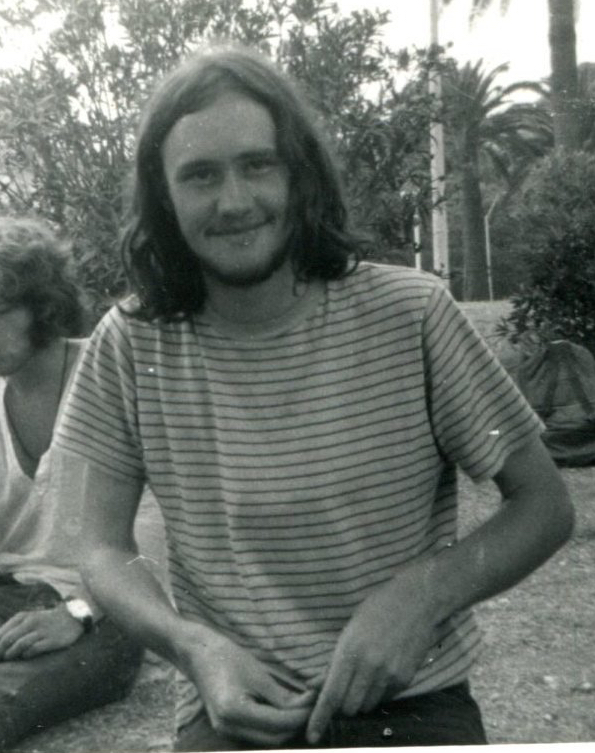

When I was twenty, I dropped out of college and travelled alone, overland to India. I didn’t tell my parents where I was until, some months after my disappearance, I sent them—from Mount Abu—one of those thin, blue airmail paper letters. It was 1973 and back then it was possible to travel through Turkey, Iran, Afghanistan and Pakistan—the old hippy trail—not so much the Silk Road as the cheesecloth road.

I was away for six months, surviving on 275 English pounds that I had saved, living cheaply, getting sick and learning things they didn’t teach in school. I returned with not just amoebic dysentery and various other foreign bodies in my gut, but a whole load of ideas and experiences which would stick with me and inform my decisions for the rest of my life.

Revisiting Mount Abu

Although I have since returned to India many times, until last year I had never revisited Mount Abu. It became a place embellished with memories, a place I had described countless times to my partner, to the extent of boring her. When, in 2013, we tentatively discussed the idea that perhaps it was time we considered getting married—twenty-five years is a very long courtship—it somehow seemed essential to me that I take her there so she could see for herself the place that had been so formative for me. We didn’t know then about the Valentine’s day marriage-fest; that was a complete coincidence. An auspicious day indeed.

The forty years since 1973 have seen monumental changes in India. For a start, when I first came here, there was no bottled water—hence my falling sick so easily back then—but nowadays there is readily available bottled drinking water almost everywhere. The downside of this is the general plastic disposal problem that is threatening to engulf not only Indian cities but even remote villages.

The beauty of it in 1973 was to see people eating take-away food off banana leaves and drinking their street chai out of home-made, mud-clay baked cups which they threw on the ground to be washed away in the next Monsoon.

Usually when revisiting somewhere after such an interval, things look smaller, different, less important, don’t they—but my memory seems to have accurately recalled a great deal of it; the long winding drive up the side of the mountain on a road swarming with dirty silver-haired monkeys, the extraordinary views down over the baking plains and the wiggly river below, the Nakki lake with its leisure boats and jetties, they have all been perfectly preserved in my mind.

Saved by Mr. Areean

I quickly find the Punjabi vegetarian restaurant, the bus station, the hotel at the top of the little road by the military barracks where I first stayed. This hotel has two new stories built on its roof, and is now called the Shree Rajendra Hotel, but a brief chat with a man standing in the driveway quickly establishes that it was indeed a bungalow hotel forty years ago. The old boy in khaki shorts who used to blow a bugle under the flag of India every morning, is obviously long gone, but his flag pole is still there outside the military compound next door.

In 1973, I travelled alone and was lucky to have been befriended by Mr. Areean, the owner of the Bata shoe-store, who took me under his wing and showed me around. His shop, a small booth in the middle of the bazaar, was one of the few in which the proprietor and his customers would sit on stools rather than cross-legged on the floor. Areean was a wiry man, dressed in a sleeveless knits and slacks. He would chew Betel leaf, nuts and spices and when finished, spit the purple remains into the gutter outside his shop.

He introduced me to his family—his wife cooking in the small flat above the shop—and an old friend of his who, he claimed, used to hunt tigers in the jungle surrounding Mount Abu, who made me chili omelettes on a little wood-stove while singing old songs under his breath.

Mr. Areean showed me Mt Abu’s sites of touristic interest; the Sunset Point—so high you can see eagles soaring below you, the Nakki lake—surrounded by tourist bungalows, the exquisite white marble carvings of the Dilwara Jain temples.

Stories of the Gods

He explained to me the stories behind many of the Hindu Gods and their Avatars; Hanuman, Ganesha, Krishna, Rama and Sita. He also walked me past the graveyard of the British officers who died during the Indian war of Independence of 1857 (known as the Indian mutiny in western history books) and the piece of land he wanted to buy for a dairy farm. He was like a crafty uncle to the emaciated and sickly hippy I was quickly becoming. Without Mr. Areean, I would have fallen prey to loneliness and depression as well as the diseases of the gut which were starting to engulf me. It was he, for instance, who convinced me I should write that airmail letter to my parents, to let them know where I was.

On our way out of the Polo ground, we bump into Dr. Gyan Prakash again, and I tell him in my broken Hindi that I am looking for a Mr. Areean, the shoe salesman. He tells me that he knows the son. The father, Niralal Areean has passed away, but the son – Anil – may be here today. Dr. Prakash, says he will tell him that an Englishman called Nigel who knew his father is looking for him. I am excited and emotional to be back in this place that I loved so well, after forty years. And to think that the memories I have are real, not imagined; that Mr. Areean and everything he taught me actually happened, that I might even be lucky enough to meet up with his son.

Marrying Families

Standing by the entrance to the Ground, another old man, also dressed in white, explains to us, beaming, that in India it is not just one individual marrying another individual, no, “it is one whole family marrying another family.” This is something we are told again and again and goes some way to explaining the lengthy courting negotiations that are part of any arranged marriage. Not for an Indian a quick romance followed by a dash to Las Vegas and a hangover the next day.

There is an area of the Polo Ground which has been designated the Muslim area. It has one large tent, rather than the many smaller ones of the Hindu marriages. In it the men sit on one side and the women on the other.

Here, the weddings are being conducted one after the other; a short ceremony and then on to the next one. The Hindu tents on the other hand, are full of what seems like endless ritual. The couple have to walk around a small wood and incense fire one way a number of times, then back the other. They wear massive, sparkly head-dresses and jewelry and have flower petals thrown over them by relatives. The one thing both religions have in common, it seems, is that the entire family are present and involved, not just as witnesses but as an essential part of the whole process.

The atmosphere in both areas is bright and cheerful, crowds have gathered to walk around the ground, looking at all the different weddings, as they would at a fairground, or a Saturday market. Everywhere is lurid colour and noise; loudspeakers blare and people chatter. Children come up to us and want to shake our hands. It is only as we wander out of the gates of the Polo Ground that we realize we are the only white people there. We are conspicuously the outsiders on this beautiful day of union and harmony between the religions.

A Walk to the House of Foot

The next day, we decide to get a little more serious about our search for the Areean shoe store. Dr. Prakash’s familiarity with the son has increased my confidence that it might actually be possible to find the Areeans. As we walk into the main bazaar, memories are shooting up thick and fast, and lining up against the realities in front of me.

The rows of small stalls and shops crowd into the narrow streets which have been curling up and down the main hill of Mt. Abu since before medieval times. Many of the shopkeepers still sit on the floors of their open wooden shop fronts. Some still spit their red betel leaf chews into the gutter. Some smoke bidis; small, leaf wrapped cigarettes. There are more motorcycles than I remember from forty years ago, but it seems, much of old India is still present. The memories of this place have been repeated so often in my mind over the decades, that when something does not fit, I remark on it to my patient partner, who is, amazingly, not yet tired of me saying; “this is where I sat and had an omelette,” or “there were more vegetable sellers here.”

I have prepared some phrases in Hindi, enough to say things like; “I was here forty years ago, can you tell me does the Bata shoe store still exist?” We are told that it is now a multi-brand shoe emporium and directed further up the hill. I am frustrated that the alleys are so twisty and turny that I cannot easily lead us to the exact spot.

After a few more wrong turns, we find ourselves in front of a shop front that announces itself as “Mr. Areean’s House of Foot Collection.” This is the place.

Inside, a young man in a dark jersey, smart trousers and combed hair tells us that he is not an Areean, but a “nephew” and sales assistant. He immediately gets on the phone to his boss. While he is talking I look around the tiny interior of the store. He tells us to sit, and I put my large six-foot-three frame on the small stool by the counter.

On the wall are two large colour photographs decked in flowers and necklaces; Niralal, the father with his wife, immediately recognizable to me. They both passed away ten years ago, the lad explains.

Soon Anil, the son, arrives; a man of about forty, with a cousin and two smallish children. My Mr. Areean’s grandchildren. We look through photo books. Anil claims to remember me, but I don’t believe him. He would have been all of five at the time.

We take some photos. I tell him in my broken Hindi, that I have come to pay my respects to his father, who was a good man. I find I have glassy tears in my eyes and cannot imagine why the feeling is so strong. Until later that afternoon, when a memory of another afternoon returns to me, suddenly. A memory that has been long buried.

The God of Travel

I had been out walking with Anil’s father, my Mr. Areean, and we had stopped at a small shrine in a wall by the roadside. In the recess was a Ganesh; a garishly painted, plaster statue, about a foot tall, of a pot-bellied man with the head of an elephant. The figure sat, cross-legged in baggy pants and bedecked with garlands of flowers, shiny tin necklaces and a head-dress. Under its left foot was a scrofulous, plaster rat. Ganesha is the god of new beginnings, of overcoming obstacles, but also, Mr. Areean assured me, the god of travel. And he proceeded to tell me the story of how it was that Ganesha became the God of Travel.

“When Shiva was giving out the godheads, he tried, you see, to make it fair with all his sons, so there would be no fighting. Because with all sons fighting together, Shiva would be in all kinds of trouble with his wife again, wouldn’t he?”

I was gazing out over the Nakki Lake where, on the opposite shore, tough women in bright turquoises and pinks were vigorously slapping their laundry against the rocks. A team of green parakeets crossed the sky above us and joined the rest of their noisy colony in the trees next to the holiday bungalows. There was so much to take in. Mr Areean spat a magenta globule out from under his bottom lip and continued.

“Listen, Mr. Nigel, I am telling you the story of Shiva and Parvati and how the Lord Ganesha became the god of travel, and your mind is drifting like a vapour again, isn’t it?” I apologized and he went on.

“But there was one godhead, you see, one god-job still going, one that Shiva hadn’t given out. And they all wanted it, all the sons, it was a good one; The God of Travel.

‘Let me be the god of travel’ said one son, ‘because I have a beautiful fast horse’. ‘No, let me’, said another, ‘I have a fleet of ships’. And Shiva realized he’d have to have competition for it, it was only way fair to decide. So he said to all his sons, ‘whoever can go whole way round the world and come back to me here, the first one back, he can be the god of travel! And off they went, all the sons. Some went on horses and boats, some were very good at running. And there was cloud of dust where they had been, they were in such hurry. But Ganesh, he was left behind. He was too fat from all the sweets and cakes he liked…you see…”

Mr Areean gave me a dark smile, displaying one or two solitary brown teeth and the purple interior of his mouth where the sweet betel leaf had been chewed. Ganesha, it turned out, is also the god of sweets and cakes.

“…And Ganesha thought ‘how am I going to go around the world? All fast animals have been taken by my dashing brothers. All there is left is this old rat…” Mr. Areean indicated the rat squashed under the foot of the plaster statue.

“So Ganesh, he got on this rat, which was difficult because, well you see, rat is small and Ganesh he is pretty damn big guy. And he told rat to walk around in circle, right around Shiva and Parvati. And he did that.

Ganesh went around in a circle, all ’round his parents. And then he got off rat and he went to Shiva and he said, ‘I’m back.’

Shiva said to him ‘But you have only gone in a circle around me and your mother here — I told you to go ’round the world.’

In reply, Ganesha looked at Shiva with steady look and said; ‘my mother and father are the world.’

Mr. Areean paused for effect, and fixing me with his yellowing eyes, he continued; “And Shiva said, ‘Nice answer. You can be the god of travel.’ And that is how Ganesha became the god of travel, isn’t it?”

Circling Back

And as for my partner and I? Dear Reader, I married her. Not there and then in Mount Abu, but as soon as we could after our arrival back in England, with our loved ones gathered around us. Our two families making one big family. We’ve made our own circle around the world, you see. We first met forty years ago in 1978, separated in 1987, and finally reunited in 2003. So on our own auspicious day, our two families embraced like old friends, describing their own circles around us, and all of us part of a larger circle.

Like the dashing sons of Shiva, I have been ‘round the world. But, like Ganesh, my family is where I have found my greatest adventure.

Follow Nigel Planer via Twitter at or his website.

Art direction and images by Kevin Grady unless otherwise noted.

Edited by Robert Bundy